Domain-Driven Design

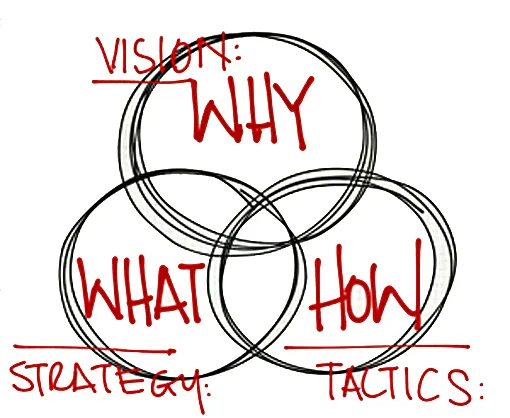

An old chess saying goes as follows: “Tactics is knowing what to do when there’s something to do, while strategy is knowing what to do when there’s nothing to do.” Although this statement is somewhat exaggerated, a more nuanced distinction might be that tactics represent the specific means used to achieve an objective, while strategy refers to the comprehensive campaign plan. This plan may involve complex operational patterns, activities, and decision-making processes that guide tactical execution.

Building software without starting with the end in mind is synonymous with not having a strategy in place. Most developers tend to focus more on the technical details than solving the actual business needs—tactics without strategy. Why though? Of course, because strategy is hard, tactics are easier, and people prefer easier tasks.

Enter Domain-Driven Design (DDD), an approach to software development first described by Eric Evans. It is a collection of principles and patterns that help developers craft elegant object systems. When properly applied, it can lead to software abstractions called domain models. These models encapsulate complex business logic, closing the gap between business reality and code.

In simple terms, DDD helps make software deeply reflect a real-world system or process. For example, let’s try modelling a bank savings account.

Modelling a Bank Saving Account

Without DDD, a naive developer might model a savings account merely as a calculator, where one can add to or subtract from a balance. That seems like the simplest approach, and everything else should just build upon that concept, right?

In reality, a savings account is much more intricate. It processes iterations over an audit trail of database transactions, which include deposits, interest accruals, and various money transfers. It’s not as if there’s tangible money just sitting on a shelf in a bank somewhere. The underlying structures of a banking system are complex, designed to cater to tax officials, actuaries, and other stakeholders that developers might not initially consider.

To develop effective software, understanding the domain it serves is crucial. You can’t create a banking software system without a deep knowledge of banking itself – understanding the banking domain. Bankers profoundly understand this system, so their expertise is invaluable. DDD aids in the creation of models that represent a problem domain. The model consists of essential concepts selected for software implementation. To achieve this, DDD emphasizes close communication between domain experts – bankers, in this case – and developers. This dialogue should revolve around the domain, ensuring domain experts aren’t merely listing desired software features. Instead, they should discuss the fundamental properties or behaviours required of domain objects. Likewise, developers shouldn’t fixate on the technicalities, like class variables or database columns, but focus on the bigger picture of the domain’s needs.

A Domain Model is an Object Model describing the problem domain. They include the domain objects in the problem domain and describe the attributes, behaviour and relationships between them.

Ubiquitous Language

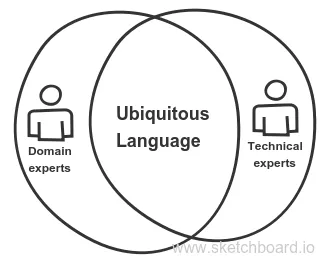

After the domain expert and developer have thoroughly discussed the domain topic, they collaborate to form a ubiquitous language. This language serves as a common medium for the entire team, ensuring alignment between the software’s functionality and the team’s objectives. The DDD ubiquitous language facilitates a clearer understanding of terms utilized by business experts. This allows the tech team to stay updated on any shifts in terminology or changes in meaning. Following this, modifications such as adding new fields on screens or columns in database tables can be executed more seamlessly.

Models and Context

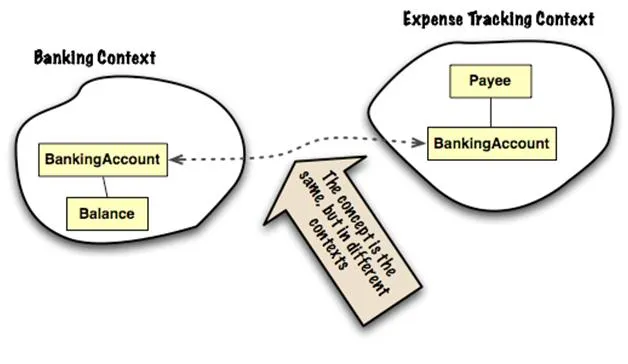

Every model exists within a specific context. This context provides a backdrop that shapes the meaning of statements, often inferred by the system’s end users. Take, for example, our savings account system: bank tellers might interpret certain terms and concepts differently than regular customers would. This differentiation in interpretation within DDD is known as a “bounded context.”

A Bounded Context (BC) defines the specific environment where the ubiquitous language and its corresponding models hold true. It offers clarity to the team regarding which elements must remain consistent and which can evolve separately. It’s crucial to note that each domain model resides exclusively within one BC, and each BC encloses a singular domain model. In essence, the Bounded Context is the very space where the Ubiquitous Language comes to life.

Bounded Context is where Ubiquitous Language lives.

Moreover, when we chart the connections between these contexts, we create what’s known as a “context map.” This graphical representation delineates various contexts. Within every context, there’s a distinct language, a standalone implementation, and an interface for communication with other bounded contexts. Such a map is instrumental in shedding light on the specific dependencies of each bounded context.

Consider the provided illustration above as a rudimentary Context Map. By outlining parts of the domain model, it highlights zones where conceptual consistency is maintained. As shown, there are areas where the two contexts intersect. The concept of a banking account, for instance, is interpreted differently across various segments of the application, leading to the utilization of diverse models. These models, despite their differences, will likely have significant interactions.

Beyond ensuring the integrity of the model within its context, the context map underscores the interactions between differing contexts. Given that the same team is likely overseeing both contexts, it’s crucial for every member to recognize and understand these divergent contexts. This understanding might entail a shared “translation map” for terms and concepts that span both models.

Domain-Driven Design in a Nutshell

To encapsulate the essence of Eric’s book, we can categorize its profound insights into several pivotal concepts:

- Knowledge Crunching: The process of distilling vast information into usable knowledge for software design.

- Ubiquitous Language: Establishing a common language that bridges the gap between technical and domain experts.

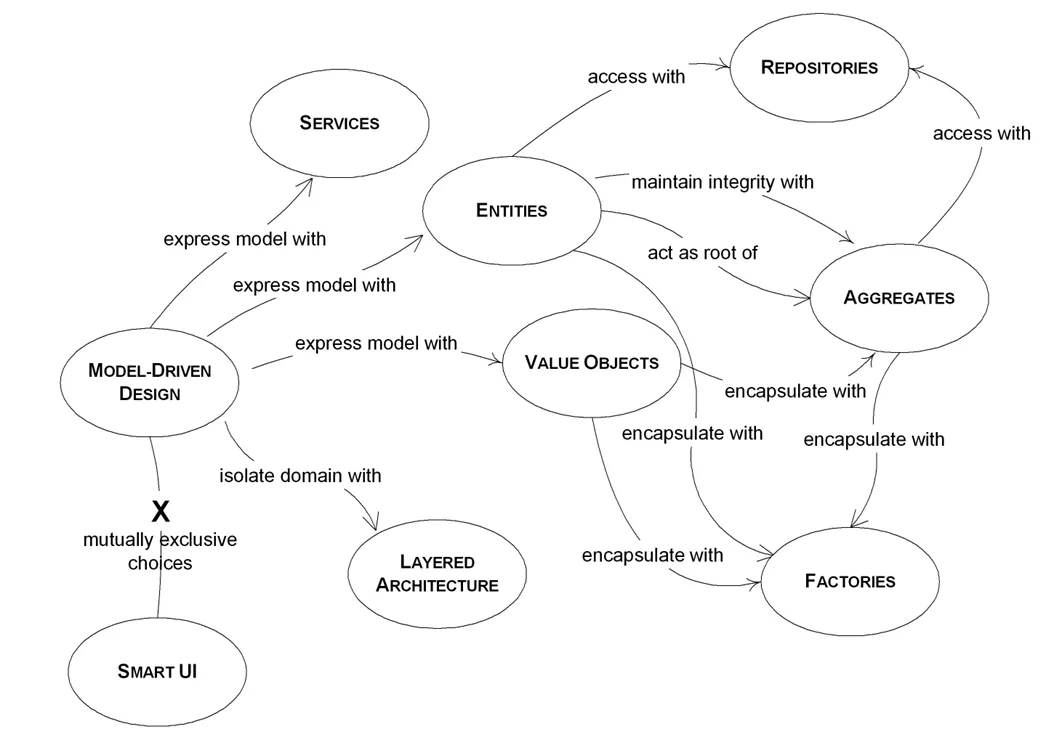

- Model-driven Design: Using a shared model as the foundation of both design and implementation.

- Implementation Patterns: This includes a plethora of patterns such as entities, aggregates, aggregate roots, value objects, strategies, domain services, domain events, repositories, and more.

- Supple Design and Refinement: The continuous process of refining the design to gain deeper insights and maintain flexibility.

- Strategic Design: Concepts like bounded contexts, context maps, core domains, and subdomains, provide the overarching architecture and strategy for domain-driven design.

It’s worth noting that to truly grasp the nuances and intricacies of these concepts, immersing oneself in the book is essential. This post serves as a primer, a window into the vast world of Domain-Driven Design that Eric has so eloquently presented.